In the waters of the Red Sea – one of the world’s most important shipping lanes – trouble is brewing.

Members of Yemen’s Houthi rebels have stepped up attacks on vessels to show their support for Hamas in its conflict with Israel.

It has led some of the world’s largest companies – including shipping giant Maersk and oil company BP – to stop sailings through the Red Sea.

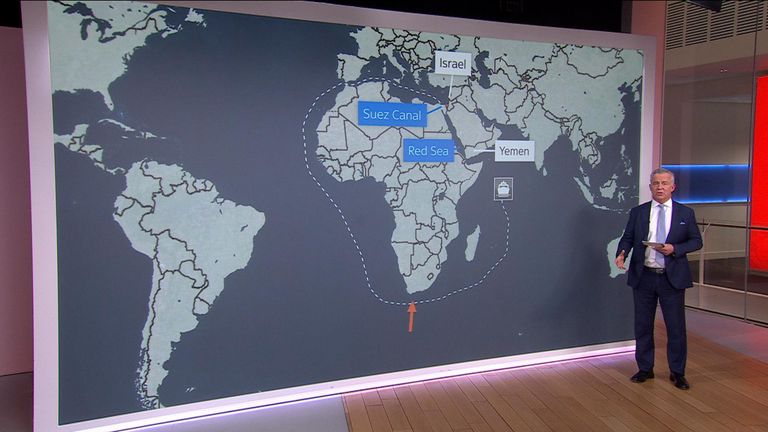

The route is used by ships to access Egypt’s Suez Canal – a major shortcut linking the Mediterranean and Asia without the need to travel around Africa – to transport natural gas, consumer goods, electricals, and food and drink.

Israel-Gaza war latest: British ship among those ‘attacked’ in Red Sea

Who are the Houthis?

The Houthis – officially known as “Supports of God” or “Ansar Allah” in Arabic – are a group of Shia Islamist rebels based in western Yemen.

The group formed in the 1990s as a movement to promote the rights of Zaidi Shias and the Houthi tribe, from which the group gets its name.

Members of Houthi military forces parade in the Red Sea port city of Hodeida, Yemen, in September 2022. Pic: Houthi Military Media

It opposes US and Israeli influence in the Middle East – with its slogan containing the words “death to America”, “death to Israel” and a “curse upon the Jews”.

Backed by Iran and allied with other Islamist groups in the region such as Hamas and Hezbollah, it has also accused Saudi Arabia of “colluding” with the US.

The death of the group’s founder, Hussein al Houthi, at the hands of the Yemeni military, sparked a civil war – the Houthi insurgency – in 2004.

Houthi supporters gather around a military helicopter in August 2023

The group, now led by his brother, Abdul-Malik al Houthi, also took part in the 2011 Yemeni revolution, gaining further territory.

Since then, it has furthered its area of influence and it now controls much of Yemen’s western seaboard down to the Bab al Mandeb Strait – the entrance to the Red Sea.

Why are they attacking ships in the Red Sea?

The Houthis have been attacking ships in the Red Sea in response to Israel’s war in Gaza.

The group, which supports Hamas, vowed on 19 November to target vessels it believes are heading to and from Israel.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

2:53

How Houthis are disrupting shipping

It has attacked several ships in recent weeks with drones, rockets and in some cases has used helicopters to drop militants on to commercial vessels.

That was the case when militants from the group captured the cargo vessel, the Galaxy Leader, in November.

Houthi rebels have also claimed responsibility for launching an attack on two ships – the Norwegian-owned Swan Atlantic and the Panama-flagged MSC Clara – using drones.

A Houthi military helicopter flies over the Galaxy Leader cargo ship in the Red Sea in this photo released in November

On Monday, the United Kingdom Maritime Trade Operations (UKMTO) noted an attack on at least one British ship off the port of Mokha in Yemen.

Which ships have been diverted?

With attacks increasing in the region, a number of companies have diverted their ships.

There are up to two million seafarers currently in the area who are now fearing for their safety, according to Joshua Hutchinson, managing director of Ambrey, a maritime security company that supports Red Sea vessels.

Oil giant BP announced on Monday it has suspended all shipping via the Red Sea as a result of the attacks, citing the safety of crews and vessels as its principal reason for doing so.

BP followed in the footsteps of shipping giants Maersk, Swiss-based MSC and French group CMA CGM in avoiding the area. Hapag-Lloyd later added its name.

Evergreen, a huge Chinese shipping company, also announced that it had temporarily suspended import and export services in Israel until further notice, citing the security risk, in addition to halting journeys via the Suez Canal.

Norway-based oil tanker group Frontline said its vessels will avoid passages through the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden for the time being.

At the same time, transit through one of the other most important routes, the Panama Canal, is constrained, with only around 24 ships passing through a day – compared with the usual 36 – due to drought linked to the El Nino phenomenon.

“That gives you a sense of the challenge global supply chains now face,” Marco Forgione, director general at the Institute of Export and International Trade, tells Sky News.

A map showing the Red Sea and its link to the Suez Canal

What goods are they carrying – and how will it impact me?

Around 12% of total global shipping traffic goes through the Suez Canal, which is the shortest route between Europe and Asia.

Primarily ships are carrying oil and liquefied natural gas from the Gulf, and consumer goods and electricals from China, Taiwan and Bangladesh.

The route is also key to food and drink supply chains, with tea and coffee being transported from East Africa, wine from Australia and New Zealand, processed frozen meat from Thailand, and rice from Cambodia.

The current crisis means adding around 10 days and 3,500 nautical miles onto journeys – forcing ships to travel south to the Cape of Good Hope and then north again around the Horn of Africa.

The diversion of oil tankers has already pushed up the price of petrol.

“About 10% of the world’s oil is tankered through the Bab al Mandab strait and with BP’s announcement yesterday, petrol prices have already gone up,” Mr Forgione says.

“But the implications of that aren’t just at the pump – they’re also key to logistics, manufacturing and industry, which means I think we’re going to see significant upward pressure on inflation and prices more generally.”

Likely increase in energy bills

Delays in natural gas shipments will have a noted impact on energy costs in the UK and Europe at this time of year as gas is used so heavily to heat people’s homes in the colder months, he adds.

The good news is that price increases and goods shortages won’t be felt before Christmas, as all vessels carrying products bought between now and 25 December are either already in the UK or close by.

But with ships delayed, in the wrong place and causing congestion at ports, knock-on effects in terms of price rises and product shortages will be felt in January, February and possibly beyond, Mr Forgione warns.

“Unfortunately there’s a significant risk of inflation increasing and costs going up for consumers – with things just escalating and getting worse,” he says.

Read more:

British destroyer ordered to join task force protecting Red Sea

Traffic grows in Red Sea as more shipping firms risk delays

The situation is likely to be longer lasting than when, in 2021, a shipping container vessel called the Ever Given ran aground in the Suez Canal and blocked the waterway for six days.

“We’re heading into the first week of the current issues and there isn’t a sudden solution we can see – even with the announcement of the American Operation Prosperity Guardian,” Mr Forgione adds.

“So it’s a different type of event and there are concerns among our members that the impact will be bigger.”

The situation in the Red Sea is another headache for the West. The US has deployed a destroyer to the region, while the UK sent Royal Navy warship HMS Diamond to the region two weeks ago.

US defence secretary Lloyd Austin, speaking on a visit to Israel on Monday, announced Operation Prosperity Guardian – a coalition to address the Houthi threat – and said defence ministers from the region and beyond would hold virtual talks on the issue on Tuesday.

Norway said it was ready to provide naval officers, while other NATO states said they were ready to consider support. The British vessel has now been ordered to join the international task force protecting ships.

Additionally, London’s marine insurance market has widened the area in the Red Sea it deems as high risk amid a surge in attacks on commercial ships, according to a statement issued earlier on Monday.