On death row, there’s the man you meet and the man you Google.

When I walked into East Block, San Quentin, there was a genial wave from inside the condemned cell of David Carpenter. His internet history has him as the serial rapist and murderer known as “The Trailside Killer”.

Raynard Cummings was on good form, mimicking my Scottish accent as he stood the height of the cell door that separated us.

“I don’t think lions and tigers should be locked up like this,” he told me, reverting to Californian drawl. Search his name and you find it’s a view formed in the 40 years since he was convicted for fatally shooting an LA police officer.

The common courtesy of death row prisoners conceals the depravity and danger that brought them here.

They all have a story, everyone as dark as the next.

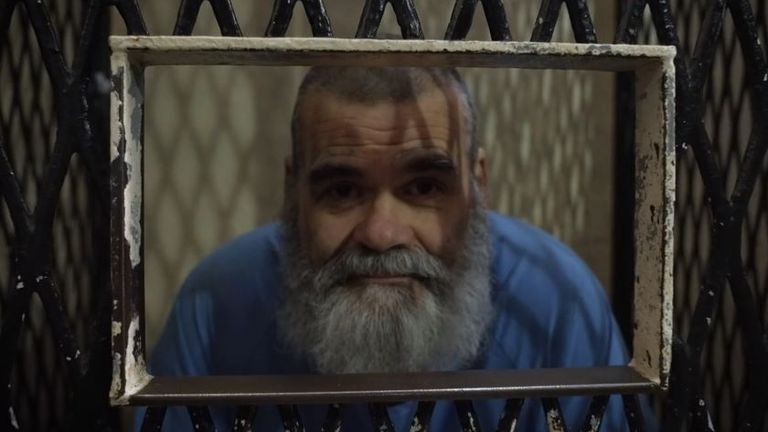

Robert Galvan – robber, kidnapper and murderer – leaned into the grated metal of a holding cage to tell me his.

“I killed my cellie [cellmate],” he said. “Actually, I wanted to come here [death row]. They gave me life for kidnap and robbery… and that made me feel bad.”

“The only way for me to get back into the court system was to do something like that, to get here you know?” Galvan said. “Now I’ve got a good lawyer, now I’ve got an appeal.”

Robert Galvan was jailed for a double murder in 1996

The 48-year-old has tattoos covering his head and inked around busy eyes that dare you to question the logic. He’d committed cold-blooded murder with the aim of a death row conviction, for the want of a good lawyer. Savagery as a strategy.

His story isn’t the only one to shock on America’s largest condemned wing – in East Block, San Quentin, there’s a disturbing personal history in every cell.

Michael Lamb, 55, a former white supremacist convicted of murder in 2008, told me: “I killed a gang member that went on Fox Undercover. I shot him in the back of the head, I executed him in an alley.”

More from Sky News:

Alabama prisoner ‘struggled’ during nitrogen gas execution

Prisoner picks firing squad death over electric chair

Gang member Michael Lamb was convicted of murder in 2002

Inside a San Quentin prison cell

Daniel Landry, 55, said: “I killed another inmate. It was either me or him and he didn’t make it.”

They are shocking tales, told in matter-of-fact terms, that feed into a sense of caged menace. The feeling is reinforced by a security infrastructure designed to keep inmates at a safe distance, which has an intensity that feels life or death.

Armed guards patrol raised walkways opposite the cells and have eyes on five floors of condemned prisoners. In their sight lines, a dress code distinguishes who’s who. Visitors, like us, are asked not to wear blue, denim or orange because these are the colours worn by inmates.

Daniel Landry killed another inmate

Prisoners can leave their cells for 20 hours a week, but only with a strip search beforehand, always in handcuffs and with a hands-on escort. When they are moved, it’s at a smart pace and with a staff shout to clear a path.

The security specifications of a death row cell mean that it’s difficult to see inside. Bars are reinforced by a tight mesh reinforcement that darkens the 10ft x 4ft box so the prisoner appears in near silhouette. A twilight existence, indeed.

Death row’s a noisy place. Conversations are held between cells and inmates compete to be heard against an incarceration soundtrack of slamming metal, keys, buzzers, barking tannoys and the faint persistence of cell TVs and electronics.

San Quentin’s 400 inmates live under the watchful eyes of guards and are escorted every time they leave their cells

On being imprisoned here, Lamb told me: “It’s inhumane the way they treat us. We’re in our cells all day long. We have to strip down naked, show ourselves and then get handcuffed to go anywhere around here.”

Galvan said: “The downside is the not knowing part. You’re just here waiting to die, you’re just here waiting on a date. We’re all just stuck, it’s like a warehouse.”

Landry told me: “Death row is a lot of cell time, dark, kind of parasitic. They make up their own rules and it changes day to day and you never know, really, what’s coming and it’s just oppressive.”

The 400 inmates left in the prison are being moved to other facilities

There hasn’t been an execution in San Quentin since 2006 and, as things stand, there’ll be no more.

California Governor Gavin Newsom imposed a moratorium on the death penalty, calling it government-sponsored premeditated murder and stating that ending up on death row had more to do with wealth and race than it did with guilt or innocence.

By the end of this summer, all condemned prisoners will be elsewhere. That’s the scheduled date to shut down death row as San Quentin has known it.

All condemned inmates – currently about 400 – are being moved to different institutions in California where they’ll be integrated into the general prison population.

San Quentin prison will become a rehabilitation centre when its death row closes

Prisoners can only leave their cells in handcuffs

Death row will be repurposed in a facility renamed the San Quentin Rehabilitation Centre.

The condemned wing will also be dismantled at the Central California Women’s Facility, where female death row inmates are held.

Transferred prisoners will still have a death sentence but, in practical terms, they will serve life without parole.

Lieutenant Guim’Mara Berry, of California’s Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, told me: “They are being moved so that they can start to pay back court-ordered restitution and be out of handcuffs. The value is in giving a person a sense of purpose.”

“I truly believe that knowing someone is attempting to change their lives is important, even if they don’t have an actual release date.

“It will foster better mental health. These are the type of things that make people want to change. We want to bring down stress for our staff and create a safer environment.

“That will allow (the inmates) to start paying back restitution to their victims and that will give them the ability to start taking responsibility for their actions.”

San Quentin prisoners can spend 20 hours a week outside their one-person cells

On the prospect of being moved, Michael Cook, 51, who was convicted of murdering two elderly women, told me: “I don’t want nobody looking at me like I’m some kind of monster. I wanted to be treated equally like everyone else.

“I think laws being changed here might give me another chance in life.”

In San Quentin it’s life, after death row.