For a capital facing such potentially intense political convulsions, Moscow basked in a sun-drenched Sunday calm.

Red Square was closed as a precautionary anti-terror measure. A tourist asked us plaintively why he couldn’t walk across and seemed taken aback by the reference to terrorism.

Without access to Russian telegram, and which tourist watches state TV, it is small wonder he had no idea what had just transpired.

More Russia turmoil expected in coming weeks, US says – live updates

Wagner mercenary fighters in Rostov before the group’s advance to Moscow was called off

The only other indicator of the state of things, in the city centre at least, were the plain-clothes police who asked for our documents.

But people did seem shaken up.

“I was so shocked, and I didn’t know what to do, I thought I should move maybe to St Petersburg or somewhere”, said Irina.

She was from the town of Vidnoye, south of Moscow, and had seen a lot of military vehicles around her house.

“This situation was so bad, and it looked like people in government didn’t know what to do.”

“I don’t want to get into politics,” said another woman, echoing a common refrain amongst the Russian people.

“Thank God we can walk here in the centre of Moscow and everything is fine!”

Irina speaking to Diana Magnay

Read more:

How the revolt led by ‘Putin’s Chef’ unfolded

Aborted mutiny busts the myth that Putin is infallible

The former hot dog seller and thug who became Wagner boss at centre of mutiny

A man who had refused to be filmed ducked over and whispered an expletive-filled tirade against Vladimir Putin, finishing with “Glory to Ukraine!”

Brave words in Russia today – no wonder he was whispering.

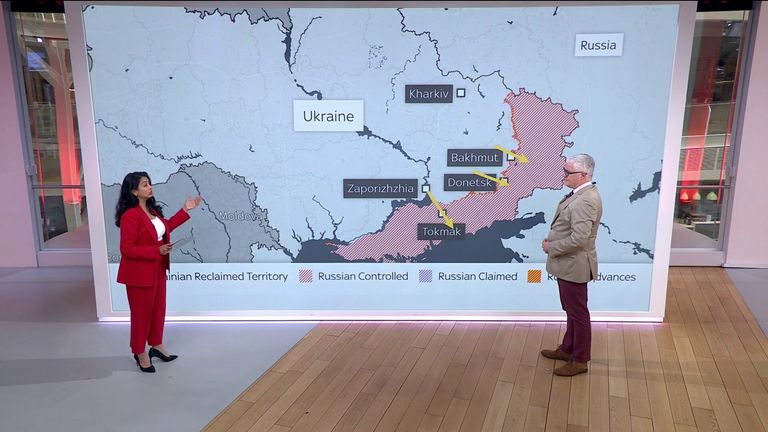

The action had all been elsewhere, in Rostov-on-Don in the Russian south, and in Voronezh, halfway to Moscow.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

3:32

Ukraine: Impact of Wagner rebellion

Ditches dug across roads to try and stop the Wagner convoy were quickly filled in. The immediate crisis was swiftly defused, its physical traces wiped clean.

But what mark will those 24 hours leave on the public consciousness and the history books, especially if this is not Evgeny Prigozhin’s final act?

In 2014, the writer Peter Pomerantsev dreamt up one of the best titles for his book on Russia – Nothing Is True And Everything Is Possible.

As I ponder the possible permutations of what Prigozhin’s armed rebellion was really all about, that phrase keeps coming back.