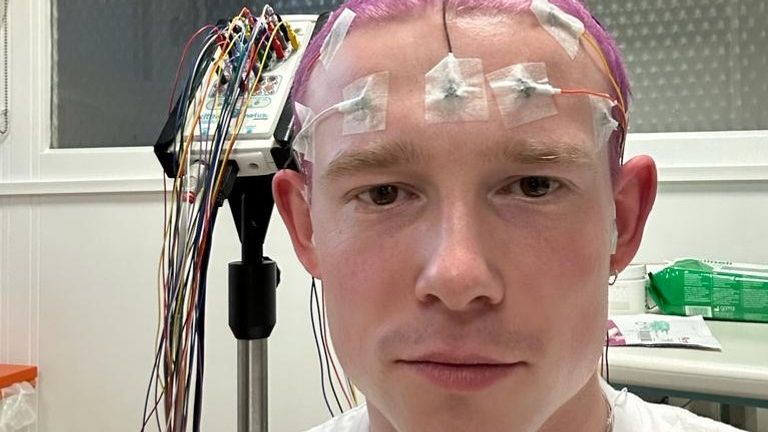

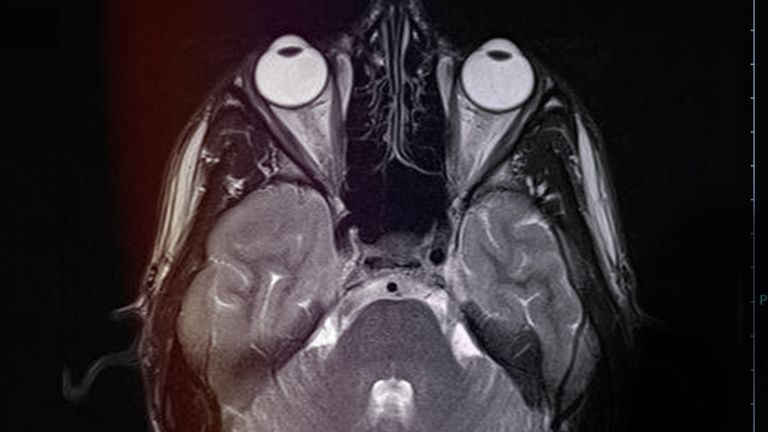

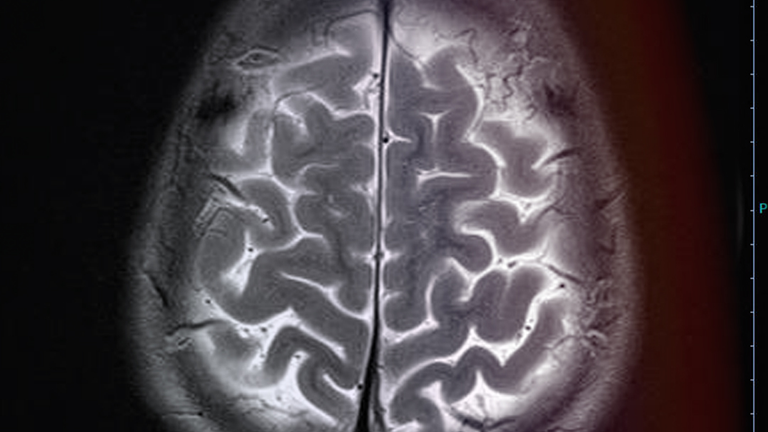

VC Pines is baring not just his soul, but his brain. Black and white skeletal images showing the inner workings of his grey matter illustrate his music, as do the harsh, eerie pulses of MRI bleeps and buzzes that have soundtracked a huge part of his life.

The alt-soul singer-songwriter, real name Jack Mercer, has temporal lobe epilepsy and synesthesia; the latter a symptom of the former, he believes, which means his senses merge and he experiences colours in connection with certain sounds or words.

He started suffering seizures while at college in London at 17, and when his epilepsy was at its worst they were happening almost daily. It was a scary time. Now 29, he has learned to love the way his brain works, and is sharing his story through his music.

“I started having what I now know were simple partial seizures, which is where you lose complete awareness and focus of anything that’s going on around you, and there were a couple of times where I would collapse… I had no idea what was going on, I thought I was losing my mind,” he tells Sky News.

“But if someone now were to say, ‘take this pill and it will be gone tomorrow’, I wouldn’t. I’ve learned how to deal with the seizures and I’ve learnt how to use them and my synesthesia to do what I love doing. I appreciate there are a lot of people who have epilepsy but aren’t mentally and physically able to do that, so I’m very lucky in the sense that I’m able to channel it. But I’ve definitely come to come to terms with it all and the seizures I have now are a lot more sporadic.”

Sometimes Mercer remembers his seizures, sometimes not. “Sometimes I only realise I’ve had one because I’m on the floor on the Tube or wherever.” He was initially treated with Lamotrigine, a typical drug for people with epilepsy or bipolar disorder, when he was diagnosed, but it badly affected his mood.

“I fell out with a lot of friends and I was completely different, basically – and I was still having seizures. So I thought I’d rather be myself and have seizures than not be myself and have seizures. So I don’t take medication for it anymore.”

He believes his brain has learned to manage things – “maybe it’s more active as a teenager, so has calmed down?” – and now the seizures come about once every few months.

While photosensitive epilepsy triggered by flashing lights seems to be the most well known, charities say it isn’t as common as most people think, affecting only about 3 to 5% of people with the condition. Common triggers are tiredness, lack of food, alcohol and stress, while other less common triggers can include “music, different sounds, smells and even reading”, according to the Epilepsy Society.

Mercer is one of 50 million people worldwide who suffer from temporal lobe epilepsy. His connected to sensory stimulation that evokes feelings of nostalgia; a smell or the touch of something that immediately unlocks a memory of the past.

“It’s often to do with my memory and I think that’s why it kind of makes me sensitive to my senses, because it’s if I smell something or if I hear something or see something, it can evoke a really strong memory,” he says. “Sometimes it’s like a memory that I’ve never remembered before, but I know it happened – so it’s linked to deja vu. And these are really, really strong, they sometimes stop you in your tracks. But that’s where a lot of the inspirations for my songs come from, they all stem from nostalgia.”

This content is provided by YouTube, which may be using cookies and other technologies.

To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies.

You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable YouTube cookies or to allow those cookies just once.

You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options.

Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to YouTube cookies.

To view this content you can use the button below to allow YouTube cookies for this session only.

Epilepsy Action’s Tom Beddow says there isn’t clear data to say exactly how many sufferers fall into each category when it comes to less common triggers such as memory or more complex activities. “Overall, everyone’s experience with epilepsy is different, and so are their triggers, if they have any.”

One vivid seizure recollection of Mercer’s was of time he spent in New Hampshire, in the US, as a child. “When I first started having seizures I would remember these massive pine trees – which is where the Pines bit of my name comes from.” The VC stands for Violet Coloured – “because most of the stuff I write and tend to gravitate towards is purple or violet in colour”.

The colours in Mercer’s brain had always been there. He just didn’t know they weren’t for everyone else – that is, until he heard synesthesia explained in a lecture during his time at the ICMP (Institute of Contemporary Music Performance).

“Halfway through, I was like, ‘What do you mean, like, B isn’t red and C isn’t green? Doesn’t everyone else see, you know, letters with colours and chords with colours?’ Apparently not. That’s when I realised the way my brain works is different.”

But Mercer is not alone. Billie Eilish, one of the most successful music artists of recent years, has also spoken about having the neurological condition, telling Jimmy Fallon on The Tonight Show it inspires her creativity.

“All of my videos for the most part have to do with synesthesia. All of my artwork, everything I do live, all the colours for each song, it’s because those are the colours for those songs.” Other artists including Pharrell Williams, Kanye West, Charli XCX, Billy Joel, Lorde and Mary J Blige have also spoken out about it.

Mercer says he has learned to harness his neurological conditions “to see what kind of colours memories can give me and therefore what kind of colours parts of the songs are, stuff like that. I try and use it as a canvas, I guess… it’s all throughout the album. Everything in there is a colour, to me.”

MRI, his debut, “encapsulates the shifts and scoops” of Mercer’s unusual brain, with Chamber, the opening track, featuring the sound of the MRI machine just like the one he remembers entering for the first time at London’s Charing Cross Hospital.

This content is provided by Spreaker, which may be using cookies and other technologies.

To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies.

You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Spreaker cookies or to allow those cookies just once.

You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options.

Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Spreaker cookies.

To view this content you can use the button below to allow Spreaker cookies for this session only.

Click to subscribe to Backstage wherever you get your podcasts

“It’s the sound of an MRI running through this chord sequence, that kind of cuts in really horribly,” he says. “But I love it.” The album touches on themes of love, jealousy, mental health and addiction, as well as neurology and nostalgia. Mercer says he hopes it might help others going through difficult times.

“I was really scared when I was diagnosed. My immediate assumption was that it was going to get worse, because the only epilepsy I knew was a ‘flash and you’re out for the count’. But it’s not been like that.

“I want to be open about it and talk about it. My songs are all about things that have happened and my memories from seizures; it’s all stemmed from me kind of managing my life while managing this condition, basically. At the same time, I do hope people can listen to it and relate and feel the same way, I guess – without feeling sad.”