The UK has more than its fair share of looming infrastructure priorities.

There’s a neglected water network that leaks sewage into rivers and clean water into the ground. A rail system in disarray after the last-minute scrapping of HS2. Not to mention roads filled with enough potholes to swallow fleets of electric cars there aren’t enough charging points to run.

All are addressed in the second five-yearly review of the UK’s key strategic priorities by the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC).

But the main priority, it concludes, is to electrify the heating of the UK’s 29 million or so homes.

As Sir John Armitt, chair of the NIC told me with a smile: “It’s literally all hands to the pumps, in this case the heat pumps!”

The main reason, according to the NIC, is one of urgency.

We have just about run out of time to switch away from gas before we miss legally binding targets to cut carbon emissions by 2035.

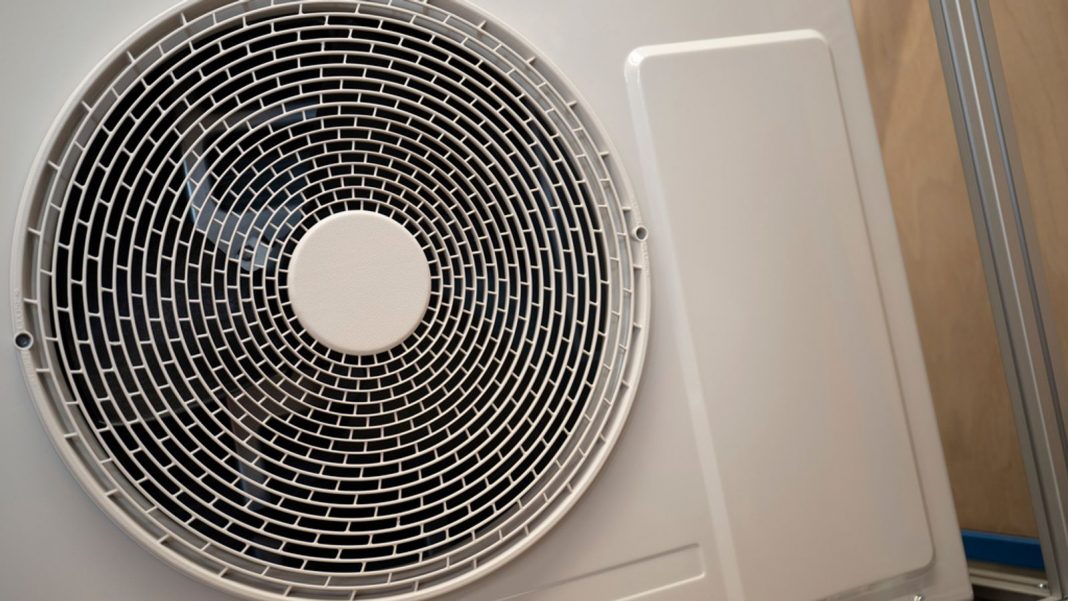

A heat pump at a German factory

But there’s also the economic opportunity in that heat pumps promise to reduce heating bills almost immediately, and halve them by the time we get to 2050 (the NIC forecasts).

Then there’s the added bonus of not being dependent on gas.

That doesn’t just avoid climate risks, but also the ridiculous price volatility of gas which, but one estimate, cost the UK economy £50-60bn extra between early 2022 and early 2023.

For infrastructure folks heat pumps are exciting.

Because they just move heat from one place (typically the air outside your home) and concentrate it in another (your radiator/hot water tank) they’re 3-5 times more efficient than a gas boiler. And when powered by wind, solar or nuclear power, they have negligible carbon emissions too.

The challenge is cost.

Read more:

UK installs record number of heat pumps and solar panels

Rollout of £150m heat pump scheme branded ’embarrassing’

For the time being at least they are on average (according to the NIC report) £10,000 more than a gas boiler to buy and install, and require a fairly energy efficient home.

But, as the NIC outlines today, with a couple of decades of subsidy for heating – just as subsidy helped the shift to clean energy generation like wind power – the switch can be made.

Consumers benefit from lower bills and a planet their grandchildren can live on.

Not everyone sees it that way of course. Companies that run the gas networks and make traditional boilers hardly welcomed the NIC’s key recommendation.

One thing they liked even less was the conclusion there was no place for hydrogen in heating people’s homes (compared to a heat pump, burning hydrogen is 5-6 times less efficient and far more expensive, the NIC found).

This content is provided by Spreaker, which may be using cookies and other technologies.

To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies.

You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Spreaker cookies or to allow those cookies just once.

You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options.

Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Spreaker cookies.

To view this content you can use the button below to allow Spreaker cookies for this session only.

Click to subscribe to ClimateCast with Tom Heap wherever you get your podcasts

The possibility of replacing natural gas with hydrogen allowed the existing gas industry to offer “hydrogen ready” boilers and a possible future for their products.

The NIC is urging government to stop flip-flopping around hydrogen (except for industrial uses) and go all in on electric heat.

The big question is of course whether this government, or the next, takes on the NIC’s heat-pump challenge.

Can they afford the billions in annual subsidy costs? Can they afford the political backlash from private homeowners if they feel “forced” to replace their gas boilers (something Rishi Sunak so recently tried to head off)?

But others might argue, given the improvements low carbon heating will make to the economy, and environment long-term, how can they afford not to?