The tension is palpable in the control centre of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO). A heart-stopping moment for every scientist and every Indian watching.

For the first time live pictures emerge of Vikram, the lander carrying the Pragyan six-wheeled rover in its belly making a soft landing on the southern surface of the moon.

There are jubilations all around, scientists clapping and congratulating each other, and with it a surge in national pride as India joins the table as a prominent player in the community of global space exploration.

Sreedhara Panicker Somanath, the chairman of the ISRO, said the immortal words: “We have achieved soft landing on the moon. India is on the moon.”

The country is the fourth after the United States, the Soviet Union and China to have a spacecraft land on the moon – but the first to be on its southern pole.

There was jubilation at mission control when the lander safely touched down on the lunar surface

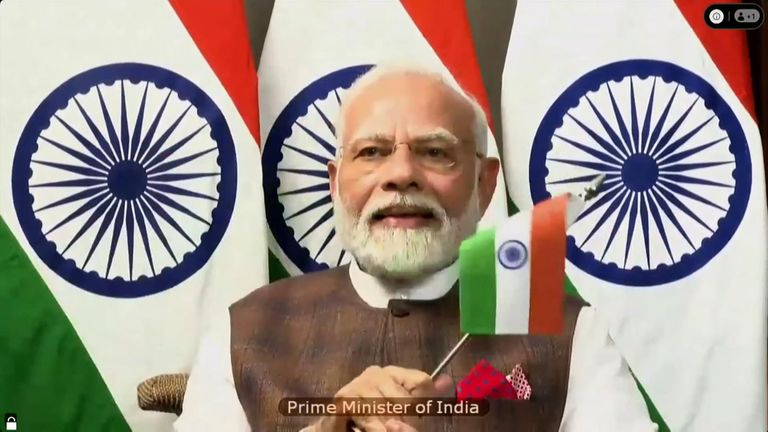

Congratulating the scientists, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said: “India made a resolve on the Earth and fulfilled it on the moon. This is a moment to cherish forever.

“India has reached the south pole of the moon, where no country had ventured so far.”

India’s moon mission has been in the making for the last 15 years with the launch of the Chandrayaan-1 in 2008. The spacecraft, the size of a refrigerator, orbited the moon for almost a year and helped determine the evidence of water molecules on the moon.

In 2019 the Chandrayaan-2 was launched but the lander deviated from its trajectory on its attempt to land and crashed into the surface. The failure was blamed on a software glitch.

The lunar south pole is of particular interest to scientists because of its permanently shadowed polar craters. Scientists believe they may contain frozen water in the rocks that future explorers could transform into air and rocket propellent.

Read more:

India made history in space – here’s what we learnt

India-UK trade deal held up by ‘sticky’ issues

The presence of water ice could also support a future space station. Launching space missions from the moon could be easier than from Earth.

Speaking to Sky News, Dr D Raghunandan, director of Delhi Science Forum says: “The southern polar region is perhaps richer in materials and a wider variety. You have these big craters formed there which would tell us about the early past, maybe how the moon was formed.

“The earlier moon missions were about adventure. These missions to the moon now are… slightly more exploratory and [taking] an interest in material resources.

“They are looking at minerals, water… thinking in terms of like we have in Antarctica today on Earth, a science mission based there which would continue to do science.”

The lander, Vikram, and the rover, Pragyan, will spend around two weeks conducting science experiments on the surface.

It will also examine the moon’s sparse exosphere and analyse the polar regolith (a blanket of loose particles and dust amassed over billions of years that cover the bedrock).

India’s space missions are but a fraction of what the United States or China spend. India’s Department of Space spends about $1.5bn (£1.34bn), while NASA’s budget stands at around $25bn (£19.7bn).

According to the ISRO, the budget for Chandrayaan-3 was $74m (£58.3m).

This is much cheaper than even fake-space ventures, like Hollywood movies Gravity and The Martian which both cost more than $100m (£78.8m) to make.

Please use Chrome browser for a more accessible video player

9:51

Modi praises India’s moon landing

Dr Raghunandan added: “Curiosity-driven science is expensive. Now, if India really has to find the money, it can. But where do you prioritise space missions and the science compared to other expenses that the country needs?

“The United States abandoned its crew missions to the moon precisely because of this. They were spending a lot of money, but it wasn’t getting the returns.

“India would be better off investing what little resources it has more on robotic missions than on crew missions. Because there’s not very much that a crew can do, which a robot cannot do.

“So we should focus more on the robotic missions to the planets, to the moon, and that will bring more dividends.”

In recent years, India’s space agency has begun earning revenue from launches carrying payloads for other countries. India’s share in the global space economy is expected to grow from 2% now to about 9% by 2030.

The commercial satellite launch market is dominated by private companies like Elon Musk’s SpaceX, Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic and Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin. India is also looking at a slice of this lucrative pie.

And with today’s success the country has become a prominent player in the global community of space explorers.